Transport historian Dr André Brett has suggested that Wellington be renamed Lowerer Hutt, perhaps to help avoid confusion within the region.

Economists Matthew Maltman and Ryan Greenaway-McGrevy have been looking at Lower Hutt’s housing boom. Their paper, released this week by the Economic Policy Centre at Auckland University, suggests Brett was onto something.

Wellington City could use a bit more Huttite thinking. And especially while Wellington’s response to the Independent Hearings Panel’s report on the district plan is still in play.

While Wellington City mulled over whether it should be legal to turn rotting wooden tents into townhouses and apartments, Lower Hutt started building.

From late 2016, Lower Hutt started a sequence of plan changes. They reduced parking requirements and introduced new zones allowing taller mixed-use developments and medium density housing. They allowed greater density within general residential zoning. And they quickly implemented policy changes set as part of Labour’s urban growth agenda – like medium density rules and upzoning requirements near public transport.

The paper tests whether those changes to zoning had any effect on building.

It might sound like testing whether water flows downhill.

The New Zealand Association of Economists surveyed its members this month. 96% of economists agreed or strongly agreed that district plan land use restrictions reduce housing supply. 94% agreed or strongly agreed those restrictions reduce affordability. And 98% agreed or strongly agreed that easing district plan restrictions will tend to increase housing supply and affordability.

But Wellington’s Independent Hearings Panel instead seemed convinced by one expert’s odd argument that zoning to allow more building, even in an obvious housing shortage, may not lead to more building.

And perhaps the Commissioners saw no reason to believe that evidence from faraway places like Auckland could also apply in Wellington.

So the Lower Hutt evidence is important. At least for those who need very specific local proof that water also flows downhill in the Wellington region.

On notification of the plan changes, and especially after the changes started taking effect, Lower Hutt started issuing a lot more consents for townhouses and rowhouses. In the new zones enabling medium density and mixed use, there was the same jump in consents for townhouses and rowhouses – and also apartments.

But perhaps that was just coincidence and Lower Hutt was only following the same trend as other councils.

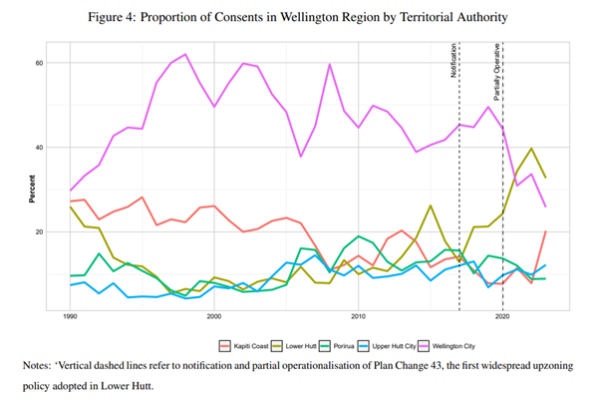

The authors used a variety of ways of checking that the zoning changes made the difference. For example, after the plan change, Lower Hutt shifted from being a moderate fraction of overall consents in the Wellington region to overtaking Wellington City.

The economists also built a synthetic Lower Hutt and compared what happened there with the actual city. This method basically sets a complicated average of patterns in other cities that tracks how Lower Hutt’s consenting rates behaved before the change. Following that ‘synthetic’ Lower Hutt after the zoning change gives a comparison.

Lower Hutt consented approximately 3260 more units than expected – a tripling the number of housing starts over the six-year period. More houses. More apartments. A few more retirement village units. And an awful lot more townhouses and rowhouses.

It also affected building in Wellington City. Because it became relatively easier to build in Lower Hutt, some development shifted to the Hutt. Overall, about a quarter of the new consents in Lower Hutt were consents that might have happened in other places otherwise.

This also matters for theories that a region may only have so much ‘absorptive capacity’ – another dubious argument relied on by Wellington’s hearings panel.

The vast majority of new consenting in Lower Hutt, about three quarters of it, was new building. It did not just displace building that would otherwise have happened elsewhere. Lower Hutt’s reforms, all on their own, provided a 12 to 17% increase in housing starts for the whole metropolitan area.

Lower Hutt then helps to keep rents in Wellington lower than they might otherwise be, by providing some of the housing that Wellington City would otherwise block. Every renter in Wellington owes a bit of thanks to Lower Hutt council.

If Wellington Council cannot see fit to propose a district plan more enabling than the economically illiterate plan proposed by the Independent Hearings Panel, the combined Upper and Lower Hutt populations could well wind up exceeding Wellington’s.

If that happens, I think we should look back at the good Dr Brett’s suggestion. The Hutts’ ascendancy ought to be properly recognised.

Wellington would become Lowerer Hutt, as Dr Brett suggested – or perhaps my preferred ‘Even Lower Hutt’. All of it would be part of the Greater Hutt Regional Council. Somes Island would of course become Hutt Island.

And the ‘special character’ that drove Wellington’s residents, and tax base, out to the Hutts could stand as warning to other cities to at least try to be less stupid than the country’s capital.

To read the article on The Post website, click here.