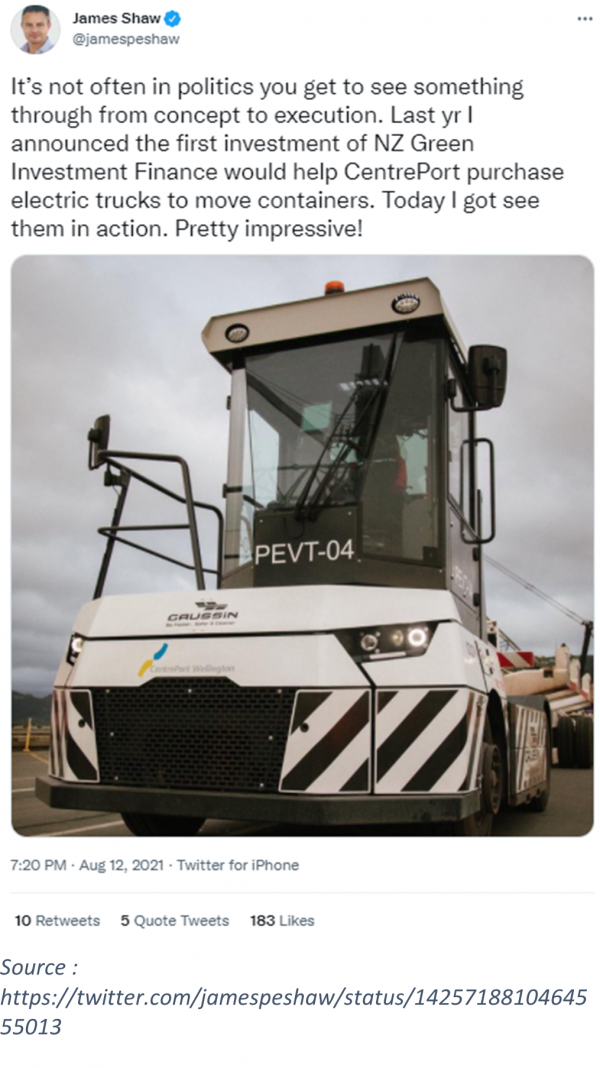

It was a small achievement but one that made climate change minister James Shaw proud. Last week, Wellington’s CentrePort deployed its first seven all-electric container movers. The port’s investment was made possible by the Government’s Green Investment Finance (NZGIF), an investment bank funding low carbon projects.

On the face of it, the new container movers look like a good way to save carbon emissions. According to CentrePort’s media release, replacing the previous diesel movers will reduce their carbon emissions by 230 tonnes per annum, which is around 8 percent of the port’s emissions.

On the face of it, the new container movers look like a good way to save carbon emissions. According to CentrePort’s media release, replacing the previous diesel movers will reduce their carbon emissions by 230 tonnes per annum, which is around 8 percent of the port’s emissions.

So, is this a good way of fighting climate change? No. But it is a good example of the pitfalls of climate change policy.

To start with the most basic problem, the Government’s green investment bank provided $15 million to support CentrePort’s decarbonisation. Let’s do the maths.

CentrePort’s total annual emissions are 2,875 tonnes.

The current price of tonne of carbon in the New Zealand Emissions Trading Scheme is $50 a tonne. This price is expected to go up over the coming years, so for the sake of the argument let’s assume a price of $100 a tonne.

For $287,500, it would be possible to remove the equivalent of CentrePort’s emissions by simply buying and shredding emission certificates.

On these numbers, the NZGIF’s investment would neutralise CentrePort’s emissions for the next 52 years.

However, that is not where the problems end. Because we have the Emissions Trading System and an emissions cap in place, the port’s electric container movers will not cut any emissions.

The reason is simple and well-known. Previously, for each litre of diesel consumed by the old movers, the port had to buy an emissions permit via the diesel vendor. Everyone using fossil fuels must have these permits. Even though they do not know they are doing it, motorists buy them at the pump with their petrol and diesel. The fuel companies bought emissions permits on drivers’ behalf and bundle the cost into the price at the pump.

The Government’s investment in CentrePort has achieved precisely nothing for the climate. Every single molecule of carbon dioxide ‘saved’ will now be emitted by someone else. We are no closer to our emissions targets and up to $15 million worse off.

It is possible that, as carbon prices increase, CentrePort might have decided to electrify its container movers anyway. Not only because of its desire to be clean and green but because it made commercial sense to do so. If so, then subsidising CentrePort is pure corporate welfare. It would have been a windfall payment for a measure that would have happened without the subsidy.

So, as an interim conclusion, the Government’s investment into CentrePort’s new electric facilities appears costly on a per-tonne basis. Plus, under the ETS, it is also futile because the tonnes of carbon, displaced at huge cost, will not even lower New Zealand’s overall emissions.

But wait, it gets worse.

Even if the green investment into the container movers had cut emissions, and even had it done so at a reasonable cost, the impact on global emissions may still be zero. How so?

Well, let’s just ask ourselves what might happen with the diesel-powered container movers the new electric ones displace. If they were not approaching the end of their lifecycles, they would probably be sold. The buyer may be another port or logistics company somewhere in the world.

And so, these old machines would still be in operation, just somewhere else. Unless CentrePort decommissioned and scrapped them, they would still emit carbon. The only hope is that they might displace some other movers with worse emissions standards.

To go one step further, even if the old container movers were physically destroyed, there is still no guarantee that CentrePort’s actions had any impact on global emissions.

The reason is the so-called ‘Green Paradox’. First described by prominent German economist Hans-Werner Sinn, it describes the outcome of some countries’ cutting their fossil fuel use while others are not.

If you are a producer of fossil fuels – say Saudi Arabia, Venezuela or Russia – how would you rationally respond to initiatives around the world to cut carbon emissions? The answer is: You would increase your oil and gas output.

The logic behind this is simple: Fossil fuel producers anticipate there will be less demand for their products in the future. Therefore, they know that the time for them to bring their products to market is limited. And thus, they will speed up their deliveries before it is too late.

At the same time, there are still many populous countries, most notable China and the US, that have not yet embarked on policies to reduce fossil fuel use. These countries will now have access to an increased supply of fossil fuels, while demand for fossil fuels is also reduced because of decarbonisation in many developed countries.

The result of both these developments is an increase in fossil fuel use and carbon emissions precisely because of concerted efforts to curb fossil fuel use in countries like New Zealand.

If that sounds too abstract, just ask yourself what will happen to the oil now no longer used to power CentrePort’s container movers. Will this oil remain in the ground, locked away and never used for anything else? Or will it still be produced by the United States, Saudi Arabia, or Russia only to power vehicles and equipment elsewhere?

To ask the question in this way is to answer it. The oil ‘saved’ in New Zealand will still be extracted and used elsewhere. It will just be bought at a marginally lower price because of the reduced demand thanks to our electrification. And that is the Green Paradox.

With that in mind, the electrification of CentrePort’s operations must now look dubious on many fronts: Nominally, it cuts emissions at a ridiculous cost. But actually, it does not cut emissions at all thanks to New Zealand’s emissions cap. And to make it worse, it is policies like New Zealand’s which encourage mineral oil producers to expedite their production and lower the global price of fossil fuels.

To make a meaningful, enduring difference to emissions the government should instead work towards a global system of interconnected carbon reduction policies. These would consist of emissions trading schemes with internationally tradeable carbon certificates. It would include cross-country cooperation on offsetting emissions via measures such as afforestation schemes. It might also mean carbon tariffs imposed on countries standing outside such schemes in order to prevent ‘Green Paradox’ effects.

At the very least, good climate policy requires politicians to understand the features and operations of their own chosen policy tools.

However, as the CentrePort example highlights, it is much easier to channel public money to some preferred emitters and then post pictures of electric vehicles on Twitter. It achieves little but the warm fuzzy feeling is priceless.