For a few months after last year’s elections, Wellington consultancies seemed to be scrambling to publish reports on city deals.

National’s coalition agreement with ACT promised long-term city deals for funding and financing infrastructure but was short on details.

The opportunity for the consultancies was obvious. The civil service is rarely nimble. The incoming government had committed to a new approach that would need working through. Lean times in government contracting were likely to reduce demand for other consultancy work. Hence the flurry of reports.

The model that everyone seems to have landed on solves an important problem, and deals work to solve mutual problems. But there’s a broader version of local deals that provides a stronger path forward for a government with broader localist ambitions.

But first, the current problem. The prior Labour Government set Infrastructure Funding and Financing (IFF) legislation for large infrastructure projects. The Crown takes on a limited amount of liability if an IFF project falls over early on, so central government will want some oversight of projects.

City deals between central and local government then help solve their mutual problem of getting successful IFF projects underway.

Financing for debt-funded infrastructure can involve special ratings districts, user charges, value uplift charges and more. Making sure that the project’s developers, local government, central government, and affected landowners are all on the same page can make sense – and city deals could help with this.

In a prior era, local infrastructure debt that was financed by special rates on affected properties required a ballot of those properties’ owners. City deals could be another way of adding democratic legitimacy to those kinds of projects, if local councils and central government wish to avoid putting projects to a vote.

And recent experience with the infrastructure version of city deals in Australia may have made that version more salient.

Talk of city deals obviously precedes the coalition agreements. For example, they were mentioned in the Review into the Future for Local Government’s report.

Just what a city deal means depends on the problem that the deal is trying to solve. There is a more interesting problem that could yet be solved by deals between central government and local councils – and between central government and iwi.

New Zealand’s government is among the world’s most centralised. Most taxation, regulation, and spending happens at a central government level.

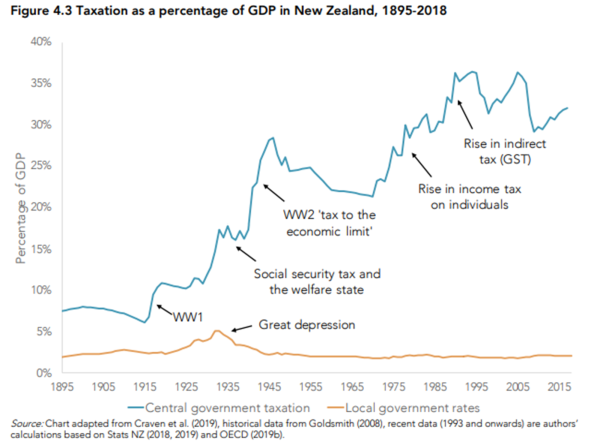

A 2019 Productivity Commission report showed that local government tax revenue, as a share of GDP, has been roughly constant for a century – while central government tax revenue has expanded considerably. Compared to other countries with similar per capita GDP, New Zealand local and regional councils’ share of overall expenditure is very low.

Relying on forums close to the people affected by decisions can have a lot of merit.

Letting policy vary between places doesn’t just mean that policy can more closely reflect the specific needs a community may have. It also provides a way for places to learn from each other – for experimentation and discovery.

State and local government in the United States form a kind of laboratory for democracy. Successful innovations can be picked up by others; bad ideas fail at a smaller scale.

Advocates for localism, decentralisation, and devolution in New Zealand quickly run into a substantial challenge. Central government officials seem always to think that handing funding and authority to local councils is too much like handing whisky and car keys to teenaged boys. And, in some cases, they may well be right.

So how might a government with a stated commitment to localism, but with understandable worries about accountability and delivery, manage it?

A different form of city deal could well be the answer.

Almost a decade ago, I coauthored a report on what we then called Special Economic Zones. But you could equivalently call them city deals, or policy trial areas.

The report proposed a framework for devolution by contract, somewhat informed by Manchester’s City Deal process - a colleague was investigating how Manchester’s deal worked while I was working on my framework.

Rather than central government telling councils what infrastructure they should want, or which services they should be delivering, the process would start the other way around.

Councils and their communities would take a hard look at which central government policies were not well suited to local purpose.

They would approach central government with a proposal for a local regulatory carveout, for a variation in the implementation of a central government policy in their area, or for devolved authority for service delivery with associated funding.

Treasury, or another appropriate agency , would work with the proposing council to come up with indicators to measure success in a trial of the proposal. They would also track any adverse side-effects.

If a project were successful, central government would benefit from higher tax revenue flowing from stronger regional economic growth, from lower long-term fiscal outlays as communities found better ways of building independence, or both. In those cases, central government should share the gains with the innovating council – and encourage other councils to consider the successful policy too.

If the project were unsuccessful, the region could shift back to the standard national framework – and we all would have learned something.

It was intended as a way of encouraging innovative councils to take the lead, build capacity along the way, and provide motivation for others to follow.

While the report talked about devolution from central government to councils by contract, every bit of it could also apply to iwi and hapū. Iwi will often be better placed than either central government or local councils to deliver improved social outcomes. They are closer to their communities. Local deals, rather than, necessarily, city deals.

The current version of city deals seems focused around a very particular current problem in making the Infrastructure Funding and Financing legislation work. I hope that the government considers local deals as part of its broader localism agenda.

To read the full article on the Newsroom website, click here.